Tokenization#

In the realm of Natural Language Processing (NLP), tokenization is often viewed as the first stepping stone to building an AI model capable of understanding human language. To take words, sentences, and ideas and translate them into a language that a machine can comprehend is no small feat. This complex task is just the beginning of the journey, laying the groundwork for an intricate system that involves embedding and neural networks to carry out effective NLP.

Overview#

NLP systems have three main components that help machines understand natural language:

Tokenization: Splitting a string into a list of tokens.

Embedding: Mapping tokens to vectors.

Model: A neural network that takes token vectors as input and outputs predictions.

Tokenization is the first step in the NLP pipeline.

What Exactly is Tokenization?#

Imagine that you’re trying to teach a machine to read a sentence, even one as simple as “I like to eat apples”. But here’s the catch - machines do not inherently know or understand any language, nor can they recognize sounds or phonetics. They are as much a blank slate as a newborn baby when it comes to language acquisition.

Tokenization is the starting point of this learning process. It is the process of breaking down a sentence into smaller units, or ‘tokens’, which the machine can then process. In our example sentence, tokenization would break it down into [“I”, “like”, “to”, “eat”, “apples”].

In an even simpler case, we could map every word in the text to a unique numerical index, creating a dictionary-like structure that might look like this: {“I”: 0, “like”: 1, “to”: 2, “eat”: 3, “apples”: 4}.

But of course, language is rarely so straightforward. Factors like punctuation, capitalization, contractions, abbreviations, and the nuances of different languages add layers of complexity to tokenization.

The Intricacies of Tokenization#

While it might seem logical to define a word as any sequence of alphabetical characters between whitespaces that isn’t a punctuation mark, that definition doesn’t hold up when faced with the complex nuances of natural language.

For example, consider contractions such as “I’m”, or abbreviations like “U.S.”, or hyphenated words such as “self-driving”. These terms are considered single words, yet when we tokenize using whitespaces as boundaries, they are divided into multiple tokens. And what about complex names like “New York”? Or languages like Chinese that don’t use spaces between words?

Beyond these complexities, there are more challenges that emerge when trying to standardize tokenization. The Penn Treebank 3 standard, a commonly used corpus for training NLP systems, tokenizes a sentence like “The San Francisco-based restaurant,” they said, “doesn’t charge $10” as such: “_ The _ San _ Francisco-based _ restaurant _ , ” _ they said* ,* “_ does _ n’t _ charge_ $_ 10 _ “ _ . _”.

Determining sentence boundaries also presents a problem. While periods might seem like clear indicators of the end of a sentence, consider a sentence such as “Mr. Smith went to D.C. Ms. Xu went to Chicago instead”. Here, the periods following “Mr.” and “D.C.” are not sentence boundaries. Similarly, identifying spelling variants, different capitalizations, abbreviations, or regional spelling differences also add to the complexity of the task. Certainly! Here’s the information broken down into bullet points:

Words aren’t just defined by blanks#

Problem 1: Compounding

Words can be combined or split in different ways, such as “ice cream”, “website”, “web site”, or “New York-based”.

Problem 2: Other writing systems have no blanks

Some languages, like Chinese, don’t use spaces between words. For example, “我开始写⼩说” means “I start(ed) writing novel(s)”.

Problem 3: Contractions and Clitics

Some words in English and other languages are contractions or clitics, like “doesn’t” , “I’m” in English or “dirglielo” in Italian (meaning “tell him it”, but it’s a combination of “dir” + “gli(e)” + “lo”).

Spelling variants, typos, etc.#

Words can appear in various forms:

Different capitalizations: “cat”, “Cat”, “CAT”.

Different abbreviation or hyphenation styles: “US-based”, “US based”, “U.S.-based”, “U.S. based”; “US-EU relations”, “U.S./E.U. relations”.

Spelling variants (regional variants of English): “labor” vs “labour”, “materialize” vs “materialise”.

Typos: for instance, “teh” instead of “the”.

How many different words are there in English?#

The vocabulary of English or any other language can be described by the number of distinct word types.

For instance, the Google N-gram corpus contains 1 trillion tokens, representing 13 million word types that appear 40+ times.

Statements you might hear about vocabulary size:

Adults know about 30,000 words.

To be considered fluent, you need to know at least 5,000 words.

Word frequency in text:

A few words, typically function words (closed-class), are very frequent (e.g., “the”, “be”, “to”, “of”, “and”, “a”, “in”, “that”).

Most words, particularly content words (open class), are very rare.

Even after reading a lot of text, you will continually encounter words you haven’t seen before.

Word Formation Processes#

Inflection: This process refers to variations in the form of a word, usually through adding grammatical markers.

Example: Verbs can have different forms like “to be”, “being”, “I am”, “you are”, “he is”, “I was”, and nouns can change form to represent different numbers: “book” versus “books”.

Derivation: Involves creating new words from the same base or root.

Example: The root word “grace” can be altered to “disgrace”, “disgraceful”, and “disgracefully”.

Compounding: This is the process of combining two or more words to form a new word.

Example: “Ice cream”, “ice cream cone”, or “ice cream cone bakery”.

These processes are also essential in forming new words. For example, the word “Google” has given rise to “Googler”, “to google”, “to ungoogle”, “to misgoogle”, “googlification”, “ungooglification”, “googlified”, “Google Maps”, “Google Maps service”, and more.

Morphemes: Stems and Affixes#

In the process of word formation, words often consist of a stem plus a number of affixes which can be prefixes or suffixes. For instance, in the word “disgracefully”, “grace” is the stem, “dis-” is a prefix, and “-ful” and “-ly” are suffixes.

Stem (grace): Stems are often free morphemes. Free morphemes can stand alone as independent words.

Affixes (dis-, -ful, -ly): Affixes are usually bound morphemes. Bound morphemes need to combine with others to form words.

Exceptions to this structure include infixes, which are inserted inside the stem, and circumfixes that surround the stem. An example of a circumfix is in the German word “gesehen”.

Morphemes and Morphs#

Language often expresses the same grammatical information in different ways. One way might be more prevalent than others, and exceptions often depend on specific words.

Plural Nouns: Most plural nouns add an “-s” to the singular form: “book” becomes “books”. However, some words have different plural forms: “box” becomes “boxes”, “fly” becomes “flies”, and “child” becomes “children”.

Past Tense Verbs: Most past tense verbs add “-ed” to the infinitive: “walk” becomes “walked”. But some verbs have irregular past tense forms: “leap” becomes “leapt”.

Linguists term these exceptions as ‘irregular word forms’. Furthermore, they suggest that there’s one ‘underlying morpheme’ (like for plural nouns) that gets ‘realized’ as different ‘surface’ forms or morphs (like -s/-es/-ren). These alternative realizations are known as allomorphs.

Surface and Deep Structure#

The terminology of ‘surface’ and ‘deep’ structure originates from Chomskyan Transformational Grammar, an early dominant approach in theoretical linguistics. Though it is not computational, it has some historical influence on computational linguistics.

Surface: The surface structure corresponds to the standard written sequence of words or characters in a language like English, Chinese, or Hindi.

Deep/Underlying Structure: This is a more abstract representation and may be the same for different sentences or words with the same meaning. It represents the semantic or ‘deep’ meaning of the sentence or word.

The understanding of these structures can be critical in NLP and computational linguistics to handle variations and complexities in languages.

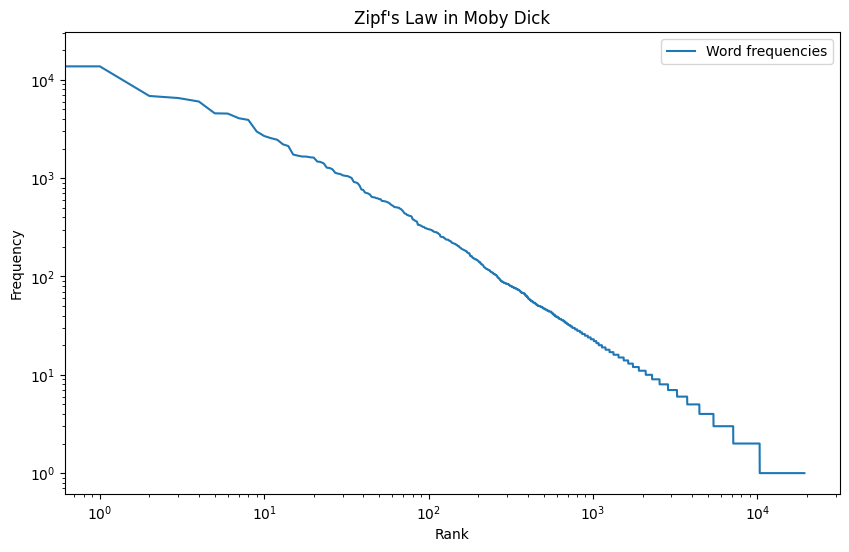

The Long Tail of Tokenization: Zipf’s Law#

Another major aspect of tokenization involves dealing with the vastness and variability of any language’s vocabulary. Even with an extensive training dataset like Google’s N-gram corpus, which includes 1 trillion tokens and 13 million distinct word types, a model will still encounter unfamiliar words.

This observation leads to a phenomenon known as Zipf’s Law, which postulates that in any language, a small number of words are used with high frequency, while a large number of words are used rarely. This distribution results in a “long tail” when the frequency of words is plotted, where common words like ‘the’, ‘and’, ‘to’ dominate the high-frequency end, and rare words make up the “long tail” of the distribution.

import nltk

from nltk.corpus import gutenberg

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load a text corpus from NLTK (Moby Dick in this case)

nltk.download('gutenberg')

words = gutenberg.words('melville-moby_dick.txt')

# Calculate frequency distribution

freq_dist = nltk.FreqDist(words)

# Prepare data for plotting

frequencies = list(freq_dist.values())

frequencies.sort(reverse=True)

# Plot the data

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.loglog(frequencies, label='Word frequencies')

plt.xlabel('Rank')

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.title('Zipf\'s Law in Moby Dick')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Fig. 72 Zipf’s Law#

The implications of Zipf’s Law for NLP can be viewed as a mixed bag of good, bad, and ugly.

The Good#

Frequently occurring words, which are often function words (like “the”, “is”, “and”, etc.), give us insight into the structure of the text. As these words appear regularly, we can train our model on them effectively, giving it a solid foundation for understanding the text’s structure and potentially its meaning.

The Bad#

Rare words, which are typically content words (like nouns, verbs, adjectives), pose a challenge. While we might know something about these words from our training data, they may not have appeared often enough for the model to fully understand their usage, meaning, or context.

The Ugly#

Unknown words, which are words that the model has never seen before, pose the biggest challenge. Despite their novelty, our model still needs to understand these words to decode the structure and meaning of the texts they inhabit.

Tackling the Challenges: The Strategies#

To counter these challenges, NLP employs two main strategies: using linguistic knowledge and applying machine learning or statistical methods.

Linguistic Knowledge#

A well-defined set of grammatical rules can help generalize the process of language understanding. In theory, a finite set of rules should be able to generate an infinite variety of correct sentences, providing the basis for the model to tackle new and unfamiliar constructions.

Machine Learning and Statistical Methods#

With the advances in machine learning and the availability of big data, it’s now possible to train models on large amounts of data. This training can help the model learn representations of words that generalize well to unseen words or phrases.